I became a little bit obsessed with Stephen King late in my teenage years. Here was a writer whose output was prodigious to say the least, who some critics seemed to hail and others seemed to hate, and whose writing seemed to quickly touch a nerve with me in the first few of his novels that I read. A couple of them were good, and one was kind of bad, but they all captivated me. There was an honesty and emotionality to them that was deeper than the surface-level horrors that were mostly emphasized in reviews that I read and in the way that King seemed to be talked about by the few people that I heard talk about him. I may have been young, but I quickly grasped that his books weren’t about blood and guts and gross-outs, but about people responding to the kinds of horrors that existed in everyday life. Sometimes in King’s novels those horrors were cloaked in supernatural clothing, but at their core they were very real, relatable, honest things.

So I read my fair share of King, and tried to get my head around what I thought about his books, and what I felt about them. But for a while there, I was scared of approaching The Dark Tower.

The Dark Tower is King’s self-proclaimed magnum opus. There are seven books in the main series along with an extra book of tales, and these were written over the course of thirty years, beginning with The Gunslinger in 1982 and ending with The Wind Through the Keyhole in 2012. These books also served as the basis for a 2017 film that was absurdly terrible, but I’ll talk about that another day. The first four books were written between the late 70s and released across fifteen years from 1982-1997, and then the final three books of the main series were written and released across 2003-2004 following an accident that nearly killed King and left the story unresolved.

These books were thick, not unlike many of King’s books, but there was something about the connectedness of them that made starting in on the series tricky. I’m all for reading a series of books, or a trilogy, or a set, but King writes long books, and they are often complicated. Seven of them? That’s a lot. And something about the way that King identified them as his most important or favorite books felt like there was a lot riding on them.

So for a while, I didn’t read them. If I didn’t read them, they couldn’t be bad. If I didn’t read them, I could, also, have plenty of time for other books (even some of King’s other books).

But eventually curiosity got the better of me, and I read them. And I loved them. And I went and saw The Dark Tower movie in theaters even though I knew it would be terrible because I knew that I loved the books.

And for some reason, over the last six months or so, I’d been feeling an urge to go back to them. It has probably been close to a decade since I first dove into the books, and now felt like the right time to revisit them amidst the closing weeks of a hectic semester.

I’ve just finished the fourth book, Wizard and Glass, and thought that pausing halfway through the series (or halfway along the journey across the Beam that leads to the Tower) might be useful to evaluate just what it is about the series that I came to love, and why I think it endures as a classic of King’s oeuvre. This isn’t really literary analysis, but rather me trying to tease out just what it is that made these stories stick for me even after all these years by looking at them each in turn.

I’m not going to try and summarize these books here, so this post may turn out to be as insular as a blog post can possibly be, given that it may require some previous knowledge of the books and their world. I’ll try and give details or as much detail as is required in order to understand some of the things that I’ll detail, but do I recognize that I’m writing to an even narrower audience than usual here. And maybe that’s just as well.

The Dark Tower #1: The Gunslinger

It’s probably cliché at this point, but it’s worth mentioning that the series’ opening line is stellar: “The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed.” It really doesn’t get much better than that.

That opening line in many ways sums up the thematic core of The Gunslinger: evocation. While the story of the first book is interesting, following the titular Gunslinger, Roland, as he pursues the man in black, what the first book is actually about is the world. One of the more interesting aspects of Giliad, Mid-World, and Mejis (the settings for these opening four books) is that they share elements with our own world. Songs, myths, and other elements of pop culture keep cropping up in the course of events—namely the song “Hey Jude.” These are often deployed in a mysterious, evocative way that tries to create a curious consonance between the world that we know and the world that exists in the books. “There’s something weird going on here, isn’t there?” these things seem to ask. I remember in my first reading of the first book thinking that it was so interesting that “Hey Jude” existed in Roland, the titular gunslinger’s, world, and wanting to know just how much of the “real” world crossed over.

But reading these through again, those references make so much less of a difference to me. They’re employed by the plot as a way of connecting the varied worlds of King’s fiction and the “real” world to the Dark Tower and its space at the center of existence, but they aren’t as dramatically curious as they used to seem to me. Instead, they seem incredibly functional to the story, not just raising a mystery but answering one: these markers don’t invite us to consider if the real world and the fictional one are connected, they tell us that this is so.

This may seem somewhat elementary, but the fact of the matter is that King is sometimes accused of being a “fluffy” writer, putting in references and nods to other things that are superfluous at best. King has been accused of being a writer that is incredibly of his time, which here can be taken to mean that he does a great job capturing technology, culture, and lingo such that some of his older books can seem incredibly outdated very quickly once the world moves on, new technologies emerge, and new slang becomes common. But the pop culture references and literary elements in the first four books of this series aren’t just window dressing or a matter of flavoring the prose with something kind of interesting—they’re essential to the tone of the story.

What I mean by this is—by connecting our world to Roland’s, King immediately sets the stakes of the saga as high as they could possibly go. He’s not communicating that there is something weird going on between our world and Roland’s, he’s telling us that everything in the story matters to us, too. The stakes couldn’t possibly be higher. We’re not just examining rifts in reality, here, Roland and his pursuit of the Dark Tower has something to do with our reality as much as his. You could almost say that this isn’t King writing a fantasy saga, but just writing an out-and-out saga that intends to examine our own reality as much as the fictional one he’s creating.

For some, this may be a small thing. King writes fiction, after all. There’s only so much that can come across to you off the page, even if you are as immersed in the story as you can be. But the scale at which King is trying to write, the way that he’s trying to deal with worldwide, universal consequences, is kind of fun. It raises the stakes, adds to the tension, and, for me, makes me curious about my place in the story. Not every book makes you think that way, but these ones do.

All of this to say that the first book does a heck of a job evoking a kind of reality and engagement with reality that sets the book apart from many that try to be like it and even from a lot of King’s other fiction. And this is, in part, what makes the first entry so great and readable.

The Dark Tower #2: The Drawing of the Three

But where The Gunslinger does an incredible job with tone and evocation, it kind of falls flat on story. You get some key events, but the majority of that first entry is dedicated to hard-boiled prose and setting up a world full of intrigue. For story and the beginning of real investment in what is happening in the compelling world that King created, we have to turn to the second book, The Drawing of the Three.

I remember that the first time I read these books I dove into the second volume expecting more of the tone and edge of the first, only to be completely surprised and even a little bit put-off by a book that was…well, more like a normal Stephen King novel. From the way that chapters were set up, to the smart, mouthy characters and the dramatic increase in dialogue and introspection from the main character, this was decidedly not the Gunslinger’s world that I knew from The Gunslinger. After getting over the initial shock, though, what I realized was that this was a much better book that was also performing a vital function of giving the compelling world that had been set up some characters and ideas that were actually worthwhile to explore within it. Roland, on his own, is an interesting character, but one with remarkable limitations. Forcing him to “draw” three companions to himself in order to enable him to accomplish his goals adds some incredible variety and character into the mix that immediately pays dividends.

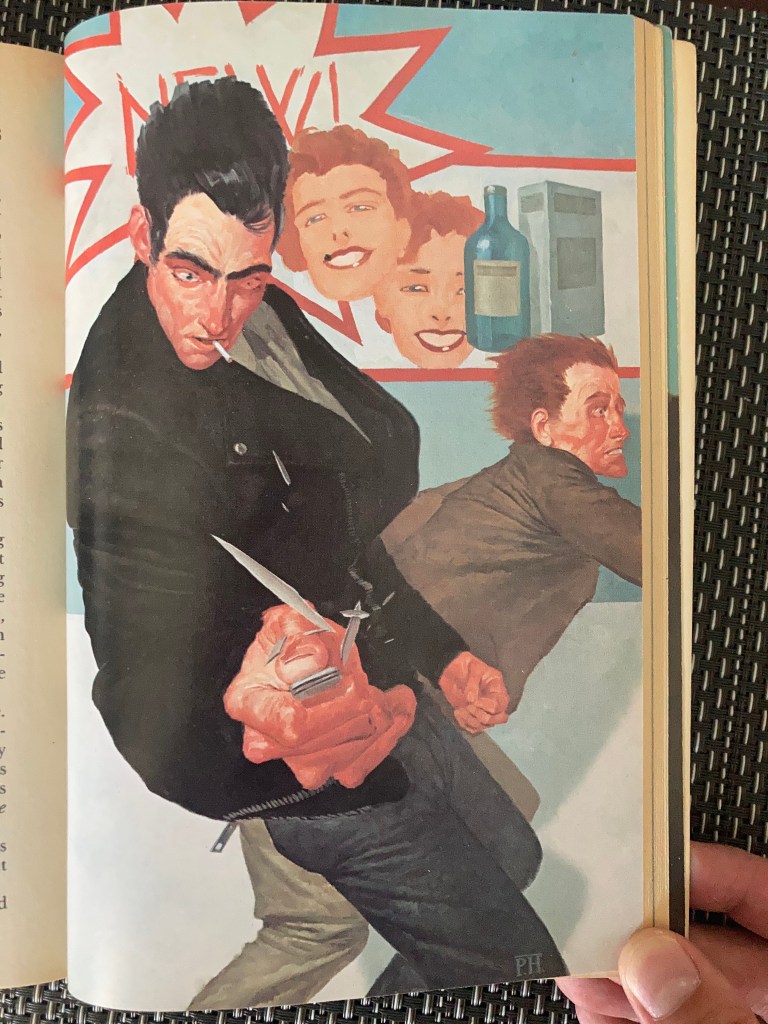

Upon returning to this book now, what I found incredible about it was the way that King focuses on a very miniscule number of events in terms of the overall plot, but explores them with such depth and density that the journey across this single volume of the saga feels richly important. In this, actually, the book is rather unlike many of King’s other books. Rather than featuring a breadth of situations and circumstances exploring an entire plot (a la Salem’s Lot) this book really focuses only on key happenings and tries to flesh out their importance in the moment and to the saga that is developing. So as Roland starts to collect companions, we get a glimpse at their importance to the world that he inhabits, and already start to see the important ways that they’ll play against Roland’s stubborn silences. Here, King’s natural talent for voices and the way that people inhabit cultures enables him to both drive us nuts with characters like Eddie Dean and the split personalities of Odetta/Detta Walker, and to show us why understanding these people through and through is going to be of vital importance. We’re going to be spending a lot of time with these folks, after all.

In one sense, The Drawing of the Three is something of a slow book. Because it only depicts a few critical events it can be perceived as somewhat plodding. But I think that this is a deliberate strength of the book’s investment in character, which then forces us to reckon with the fact that we’re not so much learning about the interesting world that we came to love in the first book, but are starting to have to inhabit it alongside characters who are more like us than we’d like to admit. Though we may not be drug addicts like Eddie or suffer from multiple personalities like the woman who we’ll come to know better as Susannah, we are all inhabitants of a time and place vastly different from Roland’s, and so can relate to the way that the exaggerations of these fictional personalities are nonetheless strained when encountering a world so familiar and yet strange as Mid-World and the like. Through their journeys we get to see understand a bit better the strangeness of Roland’s world and how maybe we ought to actually respond to it. Following along with these admittedly compelling characters forces us to confront our own fascination with that world and admit to its more frightening aspects.

What we have overall, then, in The Drawing of the Three is a deepening of the saga’s psychological complexity and depth. If The Gunslinger is all evocation and surface, Drawing is all character and reaction.

The Dark Tower #3: The Waste Lands

After creating an evocative space in The Gunslinger and bringing some interesting characters into that space in The Drawing of the Three, The Waste Lands is finally a book that lets those interesting characters run around in that evocative world. In some senses, it’s the first of the Dark Tower books that has a story in terms of having a plot and events that employ all of the varied characters in the thing that King has been setting up for two books: a journey towards the eponymous Dark Tower.

This makes for an interesting read in that this becomes the first book in the series that lets King use his talent for character and world creation together in this universe. The story retains a sense of play and invention from the first two books, but directs that into concrete actions that start to build up consequences for the larger story and the world of the story.

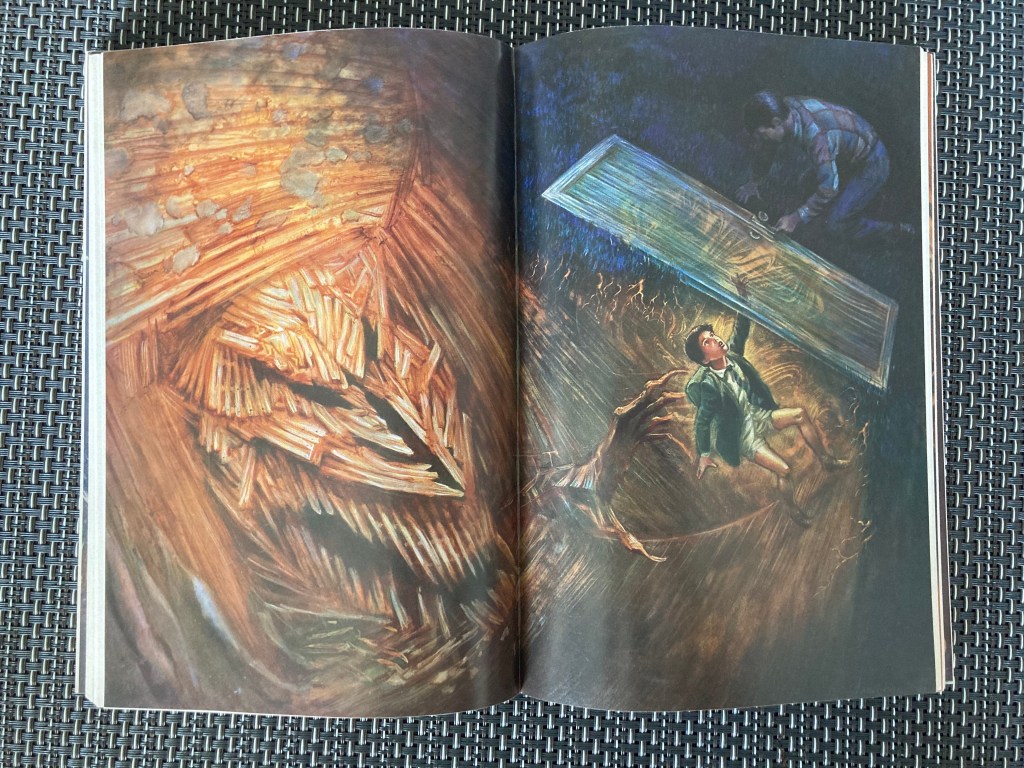

But even here the casting and drawing of the main story isn’t complete: we get another character drawn into the story world and thrown into the mix, such that at least parts of this book are reminiscent of its predecessor. Eventually, though, Jake Chambers is brought back into the world, we meet the bumbler Oy (maybe my favorite character), and the story continues on the track that had been lain before it. In this sense, The Waste Lands is the first of the books to have a story with a larger plot, but is still somewhat constrained by its dependence on the formula of “drawing” from the previous book in order to finally bring together all the varied characters that make up the series’ main cast.

None of which is to say that the book is slow, or even that it’s too similar to the book that came before it. The Waste Lands is fun still, with great characters in Gnasher and Blaine and great settings in the war-torn city of Lud. Despite some structural holdovers this book does have a mad sense of a caper in the way that some of its events play out, from an early encounter with a massive mechanical bear to the dangerous hijinks that comprise the Lud section and on. Basically, once the terms and characters of the book are set, those characters have free reign to play in the space of the story and to explore themselves and the world all at once, and the reader gets to journey with them as they discover things about themselves and each other in incredibly unexpected but natural-seeming ways. The play that takes place here, then, has the function of giving each of the characters space to feel each other out and set up the group dynamics that will empower the remainder of the series. This involves some interplay with the reader, too, getting us to appreciate the contours of each character’s talents and rough edges, and really doing the hard work of getting us to love and sympathize with these fictional people who have had a world built for them across hundreds of pages of prose before we ever really got the chance to know them.

The fun of the book, then, is in seeing everything and everyone in it finally come together into something cohesive. Here, King also showcases his talent for characterization and enrichment, for even if the characters are at times rough and their relationships only quickly established and thrown together, by the end of the book and its cliffhanger ending the reader is fully engaged. By the end of this volume the ka-tet of Roland, Eddie, Susannah, Jake, and Oy has finally cohered, and the story is zipping along into lands unknown but curious and dangerous. And when the volume closes at a breathless juncture, the reader is hooked into the world in a palpable way, even if they hadn’t been to this point in the series.

Essentially, the slow buildup and distinct feel of each of the first two books paves the way perfectly for this third one that starts to push the Dark Tower series into the territory of familiar novelistic structure. Which in turn builds up to what I think is the most complete and total work in the first four volumes of the series: Wizard and Glass.

The Dark Tower #4: Wizard and Glass

By the time you reach the fourth volume, you know and love the characters you need to love and know, and you understand the world in which they are operating, even if that world remains mysterious and dangerous. With all of the difficult parts established, then, Wizard and Glass is able to simply tell a story in a manner that is strangely complete for how actually fractured the structure of the book is. In this manner, I’d actually argue that Wizard and Glass is maybe the only real Dark Tower novel in the first four books of the series because it acts as a culmination of all of the other novelistic elements that were built up in the previous three books.

I think that this can be seen in the way that book’s rather unorthodox structure still involves us in the world and its characters—even totally new characters—with so little effort. The majority of the fourth book is actually a story within a story, with Roland telling his new friends about one of the major events in his life, the first mission he and his friends were sent on as Gunslingers, which involved the meeting of and tragic loss of his first love, Susan. So, in essence, most of Wizard and Glass is actually a flashback that doesn’t involve any of the characters that we’ve gotten to know and love.

But here is where King is really able to stretch and show his talents. Because you almost immediately fall in love with the new set of characters that he introduces, including a teenaged Roland who is instantly recognizable in terms of who he will become, but distinctive in the playfulness and occasional youthful hope that he shows. In this, the genius of the book is that the reader gets to interpret the story-within-the-story using the understandings of the main characters that we’ve developed over the previous three books. It’s King at his most trusting, expecting the reader to be mature enough and steeped enough in his world to follow along with this arguably tangential excursion.

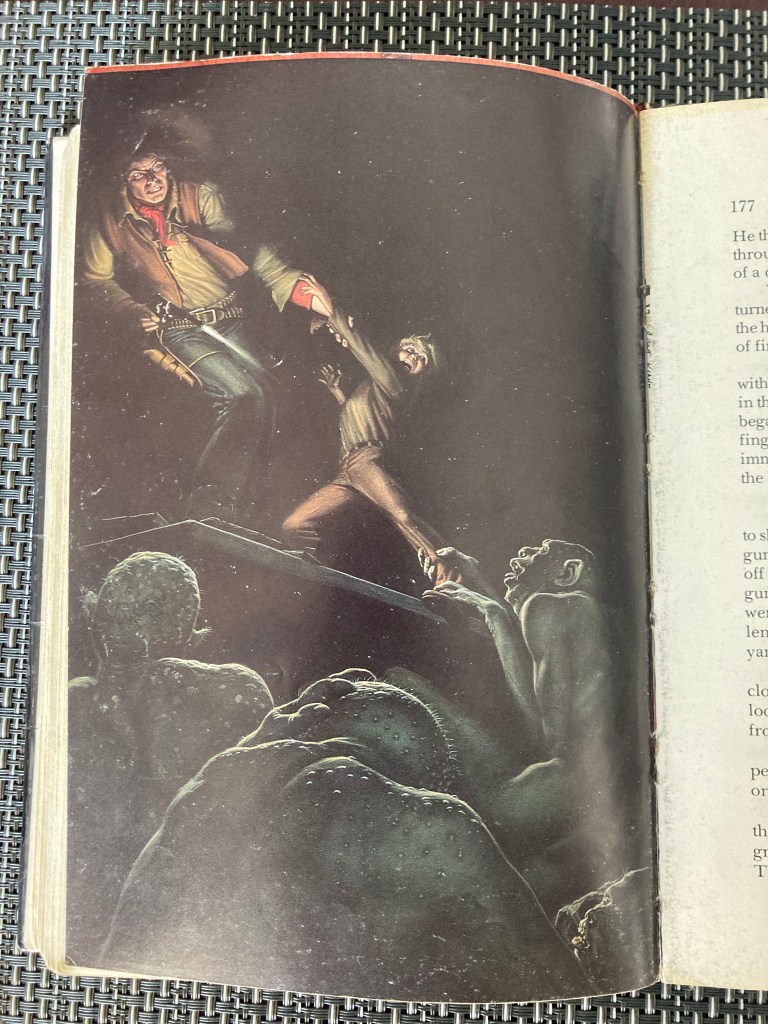

The real fun of this fourth book is that the story-within-the-story is an absolutely perfect western. There are good guys and bad guys, a town simpleton who helps the good guys outwit corrupt politicians, a saloon, and enough intrigue to make this story its own novel (which it basically is, in terms of length), all contained in a dry, dusty town—with a little bit of magic thrown in. In many senses, the story of Wizard and Glass is every western you’ve ever seen or read thrown in a blender so that all of your main tropes come pouring out at the end. But it never feels trope-laden or boring or typical. And I think this is mainly a consequence of King’s touching attention to the nostalgia of young love, which is encapsulated so artfully and carefully here. Even though we’re not hearing this flashback story from Roland’s perspective, exactly, we get little insights throughout into the way that he falls in love with Susan, and the way Susan falls in love with him, and the whole thing showcases King’s incredible talent for distilling and describing human emotions and relationships in ways that are evocative and true even as we see them for the often-tragic things that they are. I’ve always maintained that King is a master storyteller when he just gets to write great characters doing the things that they would actually do when confronted with chaotic circumstances. Here, this is what happens with Roland and Susan, even as the story around them feels meticulously plotted and deliberately constructed, the prose and the way their feelings come out for and towards one another feel as natural as can be, with as much room to grow as they might need, unrestricted (in feel, at least) by the needs and necessities of the larger plot they are contained in. Of course, we know from the start that their love is doomed and so the vagaries of the plot come crashing in at the most inconvenient of places and times, but this only adds to the intrigue and reality of their love—for what love in the real world is actually perfect, and not marred by the tragedy and beauty of inconvenience, waiting, and circumstance.

In short, the story-within-the-story of Wizard and Glass is incredible. It fits so naturally in the frame story of the larger journey towards the tower that there is almost no difference between the stories, in terms of what they contribute to the larger project. So by the time we reach the end of Roland’s recollection and return to the “present,” such as it is, we begin to see anew the stakes of the conflict happening in the fictional world, and we have a new appreciation for how each of the characters King has brought together are implicated in the ongoing struggle. And even the western aesthetic of the flashback story seems to bring something to the journey: having spent so much of the book in this simple, ancient-feeling little settlement, the danger of losing the simpler times and places where good can flourish even amidst the evil is suddenly palpable. Though we feel with Roland’s loss, we see the good that he wishes to fight for, and feel the threads of each of the varied characters coming together in support of that goal.

Onward, Towards the Tower

This, I suppose, is where I leave off. Having finished these first four books, I can say that I’m ready to dive into the final three of the main series and the one primary spin-off story. My recollection of these books is that they’re also great, but feel a bit rushed given the circumstances of their composition (which I’ll cover in my subsequent post). Still loved them, if I remember correctly, but…well, we shall see.

In all, though, I’m glad that I’ve jumped back into Mid-World and End-World and Gilead. These are superb novels with a fascinating story that also showcase the development and maturation of one of America’s greatest writers, especially in these first four books. They’re not for everyone, but for everyone they are for they are exceptional.