My last blog post was an explanation of my love for Stephen King’s magnum opus, the Dark Tower series, and a review of the original four volumes. Since it wasn’t all that long ago that I wrote that post, I won’t rehash the reasons for my interest here.

I will, though, expand on my reasons for stopping that review at the fourth book, Wizard and Glass. King wrote the first four volumes of the series between 1987 and 1997 (plus a short novella in 1998), apparently writing when inspiration struck him and proceeding with a minimum of a plan in mind. From the publication of Wizard and Glass on, though, he tended to avoid the universe of the Gunslinger, Roland, and his ka-tet, Eddie, Susannah, Jake, and Oy. He had some idea of where the story was going, and what its journey might entail, but was hesitant to jump back in. Even as some fans clamored for more, he deferred and worked on other projects.

Then, in 1999, King was struck by a van and nearly died, engaging him in a long process of recovery that had him, as a consequence, reconciling with his own mortality and the work that he was both doing and work that he had left unfinished. In the aftermath of that accident, he proceeded to finish the initial cycle of the Dark Tower series, with volumes 5-7 being published in 2003 and 2004.

What this means, in short, is that the back half of the series has a distinct feel to it, separating it from the first four books. Though there are major consistencies in character, tone, plot, and even feel, there is also an air of slight disconnect in these latter books. While the first four have a sort of searching, crawling, cobbled together aura—a consequence of the fact that they were literally cobbled together over more than a decade of writing—these last three books feel more deliberate, cohesive, and connected. This is not to say that one section of the series is better or worse than another, and to my mind there is no ultimate detriment to the way that the last three books were written and published: there is no drop off in quality. What there is, though, is some difference in how the books feel, and in what shape Roland’s saga ends up taking.

Then, interestingly, King returned briefly to the Mid-World with The Wind Through the Keyhole in 2012, a side story that fits neatly into some of the gaps left between Wizard and Glass and Wolves of the Calla. This book, too, feels distinct from all the stories that came before, even as it fits neatly into the narrative, and the prose and story are as vivid as any of the material from the rest of the series. As before: this is not bad, it’s just different.

Collectively, the final trio of novels in the main series and then this side story give a more concrete shape to the series as a whole. Though some may not love the way that the series slides somewhat into metafiction (a complaint I had the first time I read these, years ago), this re-reading helped me appreciate the way that this series not only tells a compelling and even shockingly emotionally-investing story, but also the way that King helps us reflect on his own career as a storyteller and entertainer, and our relationships to entertainment and fiction in general.

So, I saved these last four books for a separate post in part because they don’t neatly fit into the paradigm or the “feel” of the series’ first four volumes. But in reviewing each of them, I also wanted to draw attention to the distinct way that they do something for both the series and the reader’s general perception of King and his writing. Though I maintain my status as someone who is decidedly not a literary critic or theorist, I find these stories and their significance worth at least attempting to comment on here. As before, I won’t summarize them, but if there is an audience out there at all for a post like this, I hope they’ll be fine with that, anyways.

The Dark Tower #5: Wolves of the Calla

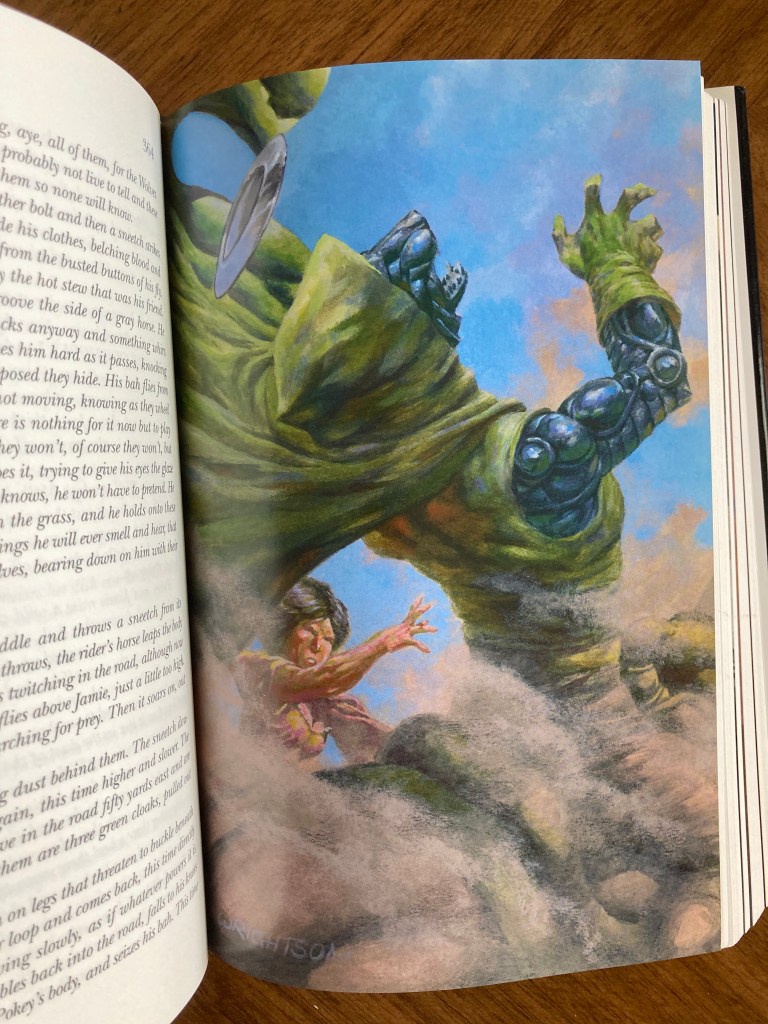

King has often been criticized for the “movie-like” quality of his work, which some have seen as a failing of his writing. Without addressing this head-on, Wolves of the Call simply jumps into the world of literature-film connections by hawking the plot of The Magnificent Seven (and, therefore, Seven Samurai) while tangling the characters of the Dark Tower series up with others from King’s works, most notably ‘Salem’s Lot. The resulting story is one that feels constantly familiar even as the characters address the story’s familiarity and wrestle with the consequences of the varied connections that they find between their own world and fictions that they knew from “our world,” before Roland drew them into Mid-World and beyond. But rather than bogging the story down in a litany of pop culture references, the whole blending of fiction, metafiction, and invention feels remarkably fresh and even prescient within the world of the series.

We’ve known from the start that the world of these books operated in a liminal space, which is even emphasized at the conclusion of The Gunslinger. What Wolves of the Call ultimately does is show us how deep that rabbit hole can go, even as the story itself engages with these issues primarily in fairly broad strokes. King seems to love playing with big character moments, hijacked references to other media, and story moments that are intimately familiar to anyone who is at all familiar with the western genre, even as he includes key and engaging discussions between his primary characters about what the heck this all means as they slowly unravel the connections between their world and the living fictions of others. And when King loves playing with these elements, the readers ultimately have fun being welcomed into a bizarro house of mirrors that has them constantly checking whether or not they got a reference, buzzed right on past it, or whether something was a reference at all. Some might find this tiresome, or even crude, but given the multilayered setup to this world, it feels surprisingly fresh and engaging. It’s also all the more impressive that King is able to do this while crafting a story that also appeals so effectively to those who might not get the references the first time around. Which, of course, is what makes his deployment of western story tropes so genius in the first place.

Father Callahan is the most obvious and most interesting addition to the cast here. The fallen priest from ‘Salem’s Lot helps provide the reader some context and the novel’s characters some crucial information that moves the plot along and introduces many of the complications that the book goes on to examine. His extended elaboration on how he ended up in the Calla and how he traveled the world’s “highways in hiding” is truly a haunting work of imagination that questions the boundaries of life, fiction, and imagination in a way that always left an impression on me, even in years past when I was never quite sure what I felt about this particular entry in the series. Callahan is also just a supreme example to call upon when pushing back at critics of King’s cinematic style and toolbox of references. Though the book itself draws upon cinematic allusions, plots, and artifacts, Wolves of the Calla invests a significant amount of time in not just continuing to dig deep into the fully-formed characters of Roland, Eddie, Susannah, Jake, and Oy, but also making Father Callahan into a living, breathing figure in his own right. Even as he calls into question his reality and metafictional status throughout this and the subsequent novels, Callahan is painted in exquisite detail as a character in his own right that you quickly come to love, trust, and appreciate. Some of this is possibly because of his earlier appearance in King’s sophomore novel; but I believe, more accurately, that it is a reflection of King’s prodigious talent. Even without grounding in the nightmares that engulfed Jerusalem’s Lot, Callahan is a force to be reckoned with and a man to be pitied in this book, and making that happen is not purely as simple as just referencing the plots of other well-known fictions.

The other fascinating thing about this particular entry in the series is that it tells a familiar western-style story directly after the fourth book, which also told a familiar western-style story, and yet manages to feel fresh the entire time. Obviously not all of the beats nor all of the characters are the same, but in theory there’s enough overlap that the books could have felt redundant. I think that the genius of King here is that there’s enough oddities happening within the world of the Calla in relation to the metafiction that the standard tropes and behaviors of the western formula, though followed very carefully, feel distinct. There’s a uniqueness to the culture of the Calla that helps, as well as the presence of the other main supporting characters, which differentiates this story from the extended flashback that comprises most of Wizard and Glass. Ultimately, I think the familiarity of the western style for the plot of this book meshes well with its surreal pop culture references to form a nice bridge between the original four books and this new, more quickly-written trilogy. We’re welcomed back into a familiar world and a familiar tone for that world, even as this book takes deliberate, particular steps to move the development of that world forward.

The Dark Tower #6: Song of Susannah

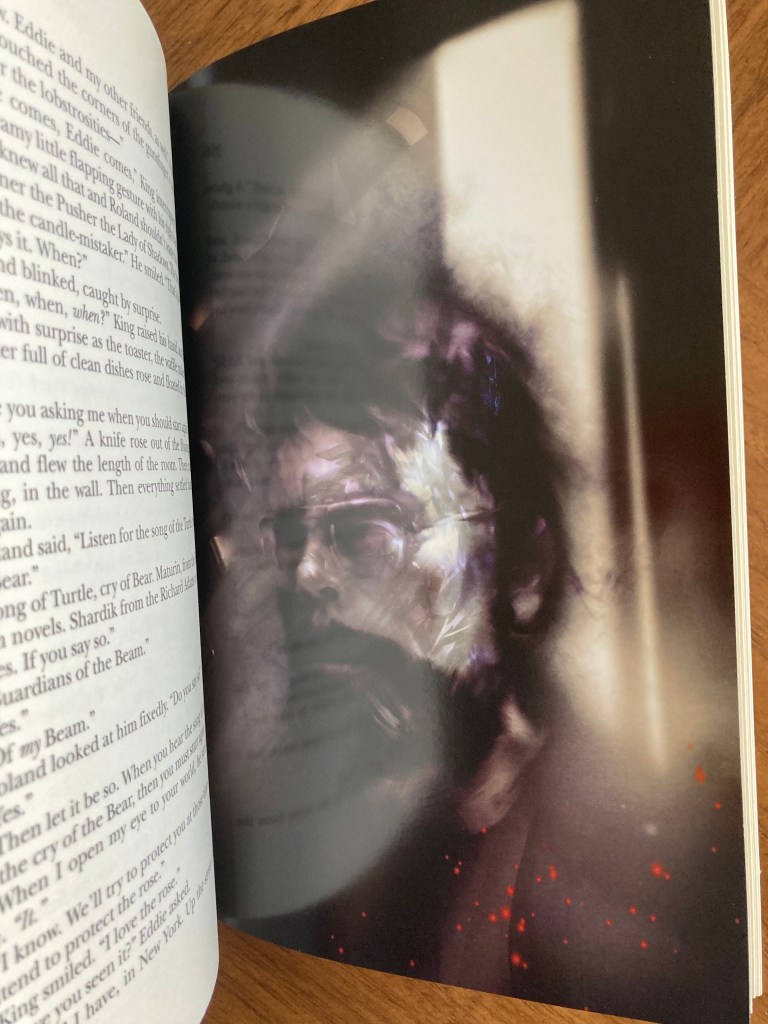

This relatively short novel—at least in the context of the series—almost feels like an interlude, even as it packs a whole lot of deep, detailed content and lore into the story. Focusing primarily on Susannah and the progression of her doomed, monstrous pregnancy, and structured like a song, the book effectively thrives at alternating between pushing some very particular plot strands forward and deepening the metafictional mystery introduced in Wolves of the Calla. If I recall, its most notable addition is finally pushing into the appearance of Stephen King as a character in his own work.

Such a move is easily criticized, and I do recall vacillating between thinking that it was a stroke of genius or a stroke of madness when I read these books as a teenager. For King to be a character in his own books—and in books that he characterizes as his magnum opus, no less—seemed simultaneously incredible and cheesy. I’m happy to say that in this re-read I found his presence shockingly comforting and even compelling, and you get a sense in his fictional appearances that he’s honestly grasping to understand what exactly led him to create this series and these characters in the first place. King has often spoken and written about the way that Roland and his companions simply tumbled into his head, and so in this work he seems to be doing some significant soul-searching about the nature of creativity and even its purpose in life, art, and beyond. The tone he strikes is one that I found particularly refreshing, too, in that he’s not trying to play literary games or mess about with form in a way that would simply be unsuited to his talents. While others have succeeded quite well at playing these games and dancing these dances, King explores these issues by doing what he does best: telling a thrilling story, one that in this case happens to be laced with curious ironies and humors in addressing his own role in the creation of his fictions. As a character, King is even a bit obnoxious, which, while certainly doing some work to construct a particular rhetorical vision of the actual author, does do some good work at presenting at least some humility on his part. One gets the overall impression, truly, that King’s role in his own fictional universe is approached with some reluctance, and even some fear.

The entire project is helped some by the sheer pace of the story at this stage, as well as the departures that it makes from the familiar form of its predecessor. Song of Susannah explores references to fiction and fictionality without directly using the structure of a film or previous plot. In essence, Wolves of the Calla uses tropes to engage us in certain questions of fiction, life, and art, and Song of Susannah uses its unique story and structure to propel those questions forward. It ends up feeling experimental, even as the story is told in King’s familiar, well-plotted style, and even as it avoids directly answering questions of form and story, the book does a fantastic job of guiding the reader through this labyrinth while also remaining accessible. There’s even a certain romance to the story, as Susannah and Eddie’s love story undergoes its most chaotic tests yet, which also demonstrates King’s range: he’s tapping into the same depths of love and feeling that characterized Wizard and Glass, but here he’s on the opposite end of a love relationship. The teenaged romance of Roland and Susan that he explored so well is here replaced with the more mature love of Eddie and Susannah, giving him new ways to explore and understand familiar emotions, just at a different stage in their development. Once again, King shows that he is a master of understanding emotion and then articulating it in highly evocative ways, pulling us in and getting us to reflect on our own experiences with these things. I remember Song of Susannah feeling like an oddball novel the first time I read it, leaving me feeling like I didn’t quite see where it fit in the arc of the series as a whole. This time, I’m happy to say, I see how essential it is at addressing the central project of the Dark Tower series and its connections to King’s other works. Though the book does not contain the hub of the universe, or let us glimpse the multifaceted nature of the worlds he creates as well as some of his other books, it connects the varied worlds of the Dark Tower to the very human relationships and feelings that his most vivid characters undergo. Without coming out and saying it, he subtly gets at the strangeness of the reader’s relationship to the multitudes of worlds they inhabit as they explore various fictions by underscoring and heightening the reality of the emotions that the characters feel as they wrestle with complicated connections and questions of fiction and reality. The book ends up being the series’ most experimental, but the main storyline carries through in a manner that emphasizes its importance: it is as if King is reminding us that for all the tangled relationships of life, love, and fiction that exist, the most important thing to keep in mind is the real emotions that we experience when in the throes of a good story. The rest, while interesting, pales in importance next to the core importance of following characters and caring for them as people.

The Dark Tower #7: The Dark Tower

At a certain point in an epic journey—across the world or through seven gargantuan books—no one actually wants to reach the end. To get there means to effectively reach a point of exhaustion and emotionality that you just can’t bear. But, of course, all good things come to an end, and though not all endings are created equal, when they work it makes the entirety of the journey worth it in retrospect, and leaves you feeling energized rather than empty. Such is absolutely the case here.

The most impressive thing about The Dark Tower is its command of emotion, and the surety of its fairness. There are many endings across the entirety of the book as various plot threads are taken up and put to rest, and more importantly as certain characters reach their own individual conclusions. King does an incredible job with each of these endings in turn, always presenting them in a manner that reads as fair and respectful of their place in the grand scheme of the story, and never giving an idealized vision or reading of these endings despite what anyone might want. The desire for a happy outcome or a romantic gesture never supersedes the needs of the story and the expectations or rules of the world as they have been established. Everyone is given their due, and each new turn in the story and every subsequent goodbye is felt hard, but also always reads true.

In bringing this story to its conclusion, King doesn’t mess around. The metafictional setup of Wolves of the Calla is explored to great lengths in Song of Susannah such that when we reach The Dark Tower there are still threads of metafiction left to explore, but their complications and vagaries in no way interfere with the pure story. Across those two previous books, especially, all of the necessary plot ingredients related to the metafictional conceit are introduced, and here in the seventh volume their necessity to the story is brought to fruition in meaningful ways. King knows that this final book is not the place for playing around; if anyone has gotten this far along the Beam to the Tower, they’re along for the ride to see what happens to Roland and the rest of them, and to reach the journey’s conclusion. It’s not that King sees the preceding two books as a place to play games or mess around with big ideas, but that the big ideas that he introduces there are here put into practical force as elements compelling the home stretch of this epic journey.

As a consequence, this book ends up being King at his most emotional, some would even say his most saccharine—though I would disagree, there. Every character is lovingly given their due across this story, even as certain people’s tales end in tragedy and others in love, King always lingers just long enough to properly care for them in his world and in the mind of his reader’s. Truthfully, I’m not sure I’ve ever wanted to cry more than I have re-reading this book and having to say goodbye to so many of my favorite fictional characters. If anyone ever doubted King’s ability to create human beings out of thin air, reaching the end of this series lays all of those doubts to rest as you are forced to confront the ephemerality and mortality of the varied stories and people you have come to love so much. Without overdoing it, King leans into these moments and feels them right alongside the reader; after all, these are some of his closest friends, too.

I won’t say too much about the book’s ending, which I’ve heard is controversial to some. Personally, I felt it fitting, even perfect. Sometimes journeys are their own kind of reward, and this book rewards that impulse in a variety of important ways.

The Dark Tower #4.5: The Wind Through the Keyhole

One of the best things about the Dark Tower world is that there are so many areas of its map that are hinted at but left unexplored in the main series, and so many slight gaps in the narrative that are begging to be filled in. This side story does just that, telling a story within a story during a time of ambiguity between Wizard and Glass and Wolves of the Calla.

The impressive part of this book is that it showcases King dabbling in telling stories about storytelling, but this time without resorting to the kind of metafictional games that were woven into the main series. Rather, he engages with the fairly simple form of setting up a frame story, a flashback story, and then on top of that telling a separate, relevant story that takes the form of a popular fairytale from Gilead. Nesting these narratives within one another provides a fun way for the book to meditate on the mystery of story, the importance of the lessons that we learn from stories, and the beauty that the telling of a tale can bring into the life of the listener and the teller alike.

That the varied stories present in this book are all very good and well-told only compounds the fun that can be had in what is honestly a pretty quick read. Given that most of the book’s time is actually spent in the fairytale, there isn’t quite as much engagement with Roland and the familiar crew as one might expect, but the time we do spend with them is sweet and satisfying, and makes the frame story and the fairytale somehow even more interesting, as the reader works to piece together their significance for the strange situation that the heroes find themselves in at the work’s outset. In the end, the book feels like a perfect little dip back into Mid-World and its complications, done in a way that doesn’t complicate the story at large or raise the stakes in any tricky way. It’s a story, told well, that underscores the significance of stories. That King does this in a book that sees him returning to his longest-running and deepest story is, perhaps, only appropriate.

Having Reached the Tower

Summarizing the impact of a massive series of eight books and thousands of pages would be, I think, something of a fool’s errand. Having reached the journey’s end again, I don’t know that anything I could say to wrap this up would be adequate at communicating the enjoyment that I got to experience, or the way that these books (especially #7) made me feel, and how surprised I was at just how important these stories and characters were to me anew. All I can really say is that I loved my time in this world again, and am glad that the impulse struck me to dive back into these stories. They’re certainly not for everyone, and getting through all eight books is most definitely a commitment of time, energy, and heart. But for those who engage them, these stories are endlessly rewarding.